1000Xresist Is A Game For A Post 2019 Hong Kong Protest Generation Of Diaspora Children That Doesn't Exist Yet

15 5月 2024

This article discusses the illusion of the North American immigrant dream for cultural refugees, the exhaustion of living under Han Chinese families, police violence, the mixed legacies of the Hong Kong 2019 protests, and the cycle of parental abuse and trauma in Chinese diasporas from a Chinese Indonesian perspective. There will also be unmarked spoilers for gameplay and story.

Associations

I have three stories to tell.

1:

An art gallery in San Francisco, 2016. I was visiting some friends and took the opportunity to see an exhibition of rare paintings by Monet. In the main hall, a Chinese mother was carrying her toddler on her shoulders to look at some Western paintings. The mother kept telling the kid that she didn't understand what she was looking at, but she told the kid that it was important to take it in.

2:

Central, Hong Kong, 2013. I was traveling between Chicago and Jakarta, and I had a day to just walk around the city-state all by myself. I've never traveled alone before, always with friends and family. I wandered around and found an independent bookstore where I found Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities. The book was about Marco Polo describing the cities he visited to Kublai Khan, but they're all descriptions of some aspect of Venice. Everywhere I looked and walked, I saw Hong Kong as refractions of the cities I've visited -- it makes everything familiar and strange. Almost like a second or third home but not quite. Hong Kong became one of my favorite cities to visit.

3:

Lunch break at a British university, 2019. My parents said on Whatsapp that these Hong Kongers were doing too much in 2014, but now? It was ridiculous, and the cops were right to tear gas them. I closed the app and scrolled through Twitter, only to see an old woman holding the British flag in front of a militarized Hong Kong police force. Sinophobic tweets from Hong Kongers were everywhere, people begged Donald Trump and Mike Pompeo to save Hong Kong from communism, and Qanon tweets mixed with desperate pleas for help. I closed Twitter too.

The first memory is of my alienation from the Han Chinese American diaspora. It would be unfair to extrapolate from this one family, but I have always remembered this scene. It was echoed in some of the Chinese American literature I read -- and I didn't get it.

I didn't understand the obsession with fitting in. My Chinese Indonesian experience showed me that I would always be a foreigner in my supposed homeland. My heritage was censored and suppressed. We died to be Chinese. Why did this mother want to tell her child to absorb as much Western art as possible? This irrational, unsympathetic anger made me realize that my experiences will never be relevant in Chinese American discourses, and I've come to accept that years later -- I'm not Chinese American, and my commentary on their concerns is bunk.

I associate the concept of Hong Kong with the second memory. It's a city I've never lived in, but I often dream about it. Hong Kong is a symbol of struggle and identity for the Chinese diaspora around the world, whether you like it or not. It's also the home of Bruce Lee, who tells us to "be like water making its way through cracks". I watched its dramas and movies religiously, telling us that everyday life is as interesting and artistically capable as action and science fiction flicks. Hong Kong has influenced me as a person over the years, both culturally and politically.

But I never realized that this aspiration would also break me. The third memory reminded me that even though I was far from the battlefields, I can still hear the echo of screams in Yuen Long and see the blood spilling around Prince Edward Station. The siege of the universities, the mysterious deaths of Hong Kongers at the hands of the police, and the forced confessions of the Causeway booksellers are still fresh in my mind.

It was too recent for me to think about 2019. I needed a few more years and maybe a few more drinks to reflect on what could've been done. There's too much to unpack, especially when the world hasn't really come to grips with the geopolitical situation surrounding China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Nevertheless, 1000xRESIST came out.

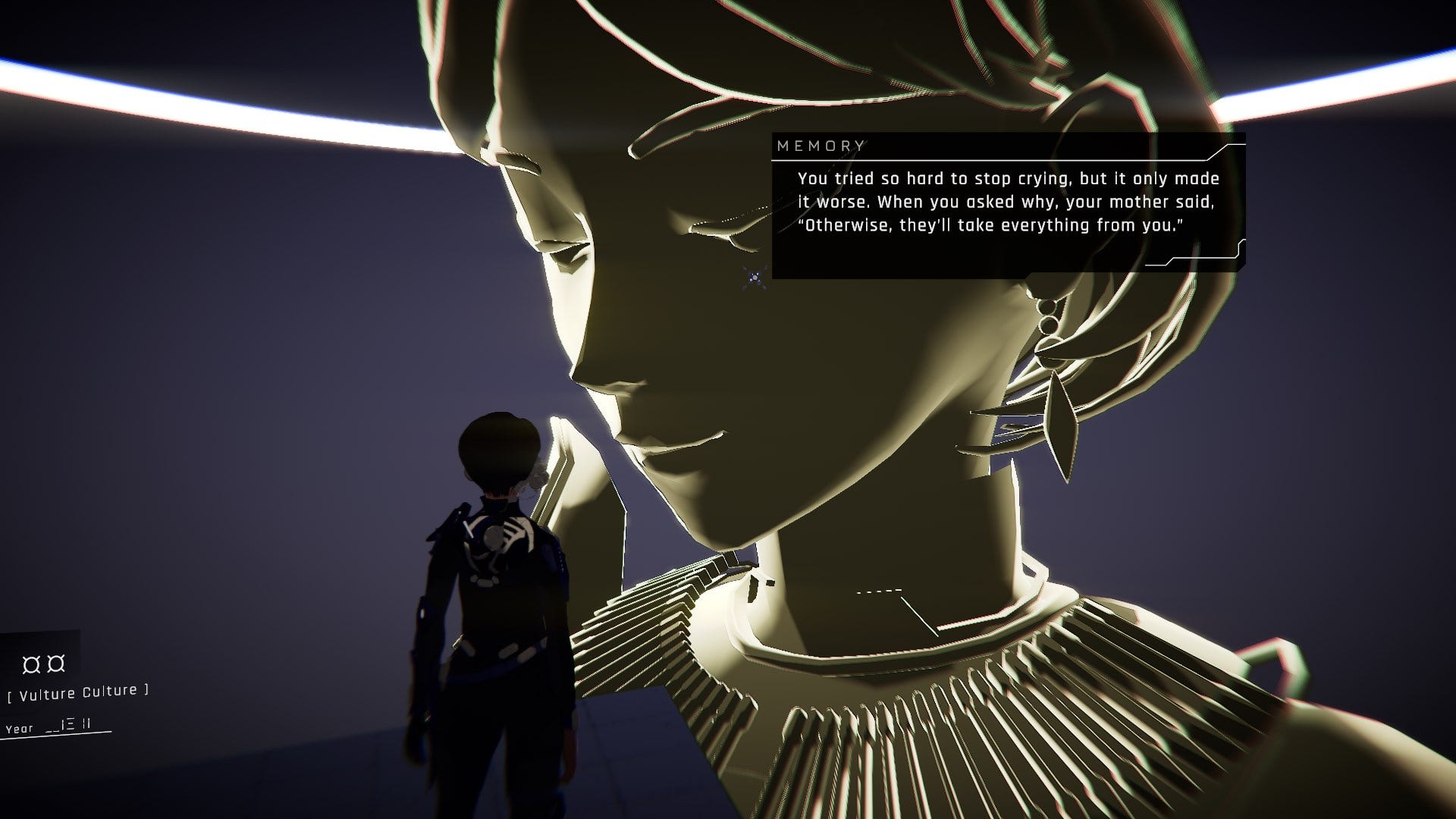

The game follows Watcher, a clone of ALLMOTHER whose sole mission is to join communions with other clones to remember the memories of their one god. These memories are supposed to portray ALLMOTHER as an omniscient figure, but it turns out that their god is Iris, an angsty teenager whose parents moved to Canada after the 2019 Hong Kong protests.

The first actual level of the game is a school colored in amber. Soldiers decked up like Master Chief linger in the corridors, criticizing Iris for her theories of "socialized immunity" and her reckless actions. Watcher needs to get to the gym, but the gym is bugged out in the communion. She learns from Secretary (a flying object partner) that she must find a way to connect memories and after encountering a floating photo of Jiao on the rooftops, the player can now teleport between different time periods -- back to when the school was actually a school (the year is 2047 when Hong Kong is slated to officially become part of China) and not a quarantine chamber for soldiers.

Students can only see the Watcher (and thus the player) as Iris, so they chat about things that weigh on their current lives. They bicker about school grades, the Occupant alien outside the high school, and whether washing their hands will even help against the alien airborne virus. When people cry uncontrollably, it can be a symptom of the virus. Those who are not infected use eye drops and hope for the best. Everyone must hold back their tears or they could be suspected of carrying the virus. But despite these existential threats, students and teachers try to do their best and go about their daily activities. Some lose their minds and pray to the alien to pardon their family members. Others immerse themselves in pointless Model United Nations meetings.

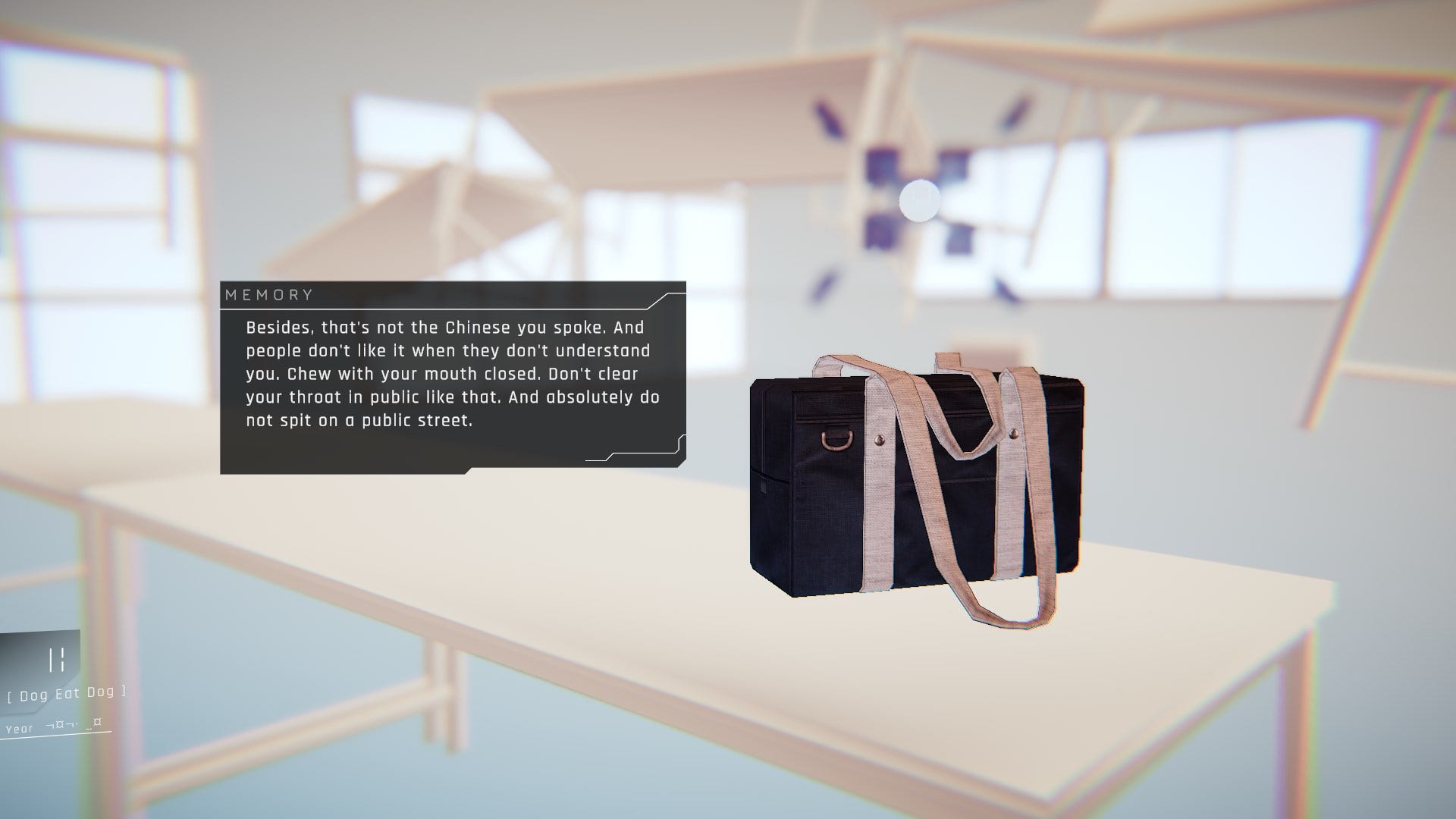

Iris, on the other hand, is too comfortable with the situation. She's been taught from an early age never to cry or show her feelings, or she'll lose everything. White students already see "Asian" students like her as model minorities, too serious about grades and the future. Iris bottles up her feelings and criticizes Jiao for not doing the same.

Jiao is a nice and sweet girl who seems to have moved from China and is still unused to the weather and linguistic climate of Canada. In a conversation, we learn that she and her parents learned English by watching true crime. But her accent is still strong, and she keeps using Mandarin Chinese for words she doesn't know, to the chagrin of Jiao who only knows Cantonese. Jiao likes Iris enough to ask her out for the dance.

But there is a barrier between the two. No matter how close Jiao wants to be, Iris pushes her away and reminds her to speak in the language of the country she had just moved into. And I feel every cut that the game delivers because I've done that to other people and other people have done that to me.

The first chapter of this game is an honest, brutal examination of how diasporas and international students don't really know how to talk to each other. Iris and Jiao don't understand what the other needs, and so they hurt each other. Despite the science fiction veneer, I ended up thinking that the game might be about diasporas struggling to assimilate in Canada -- a close friendship between two outsiders who overcome their differences and connect.

The communion in the next chapter also focuses on Iris's troubled relationship with her parents, which makes me wonder if the game was just gonna be about diasporas. I'm not sure why there was a science fiction sheen to all this: cloning technology, the so-called Orchard which is a hub world full of prayer rooms and shrines, and a faux religion calling Iris their ALLMOTHER. Wouldn't all these elements distract the player from focusing on a heartfelt story about how a Hong Kong family tried to start over in a democratic country, only to find that such a dream was not available to them?

I was thinking that the game was going to have the kind of story that movies like Everything Everywhere All at Once and Past Lives try to explain to younger diasporic generations and other moviegoers: East Asian immigrants don't always fit in with the ruling classes, and they often develop a perspective that most people find alien but still valuable to hold on to. They are the artistic voices of immigrants who say that life here has been hard and full of regrets, but they're still grateful to have a new life. If only other generations and races could connect and understand us, the suffering necessary to reach this state of understanding would be lessened. So, I didn't think the game would be anything more than that: I just assumed it would be a yuri story about Iris and Jiao from the past connecting with Watcher and teaching her how unique and beautiful the diasporic perspective on life is, even if the conflict leads to some tragedies like the Hong Kong 2019 protests every now and then.

I let my guard down. I talked to several people who said something similar. We all thought this would be another story of diasporic exceptionalism fictionalized and allegorized through science fiction tropes.

The science fiction elements are, however, are an extension of the memories of the 2019 protests.

Before any communion takes place, the player can take the opportunity to explore the Orchard. As they get lost by poorly designed signs and an honestly too large map, they may stumble upon interesting conversations between the Watcher's sisters. The clones speak to each other in a coded language taken from ALLMOTHER's poetry: for example, "hair to hair" means that each clone is born from Iris's hair. Each is a walking acolyte, ready to present their interpretation of a line of poetry or the selfless acts of their god.

Or some are just willing to slack off or kiss one of their crushes. Everyone may be a clone of Iris, but there are mutations that set them apart. This society of clones is not as cohesive as one would imagine.

Each clone is also assigned a function and then color-coded accordingly: the Fixer and anyone who are wearing green are good at tech, the Knower and her followers are dressed in purple and archive knowledge of human history, the Healer and her students in green birth new clones, Bang Bang Fire and the orange soldiers she trains do drills to protect the Orchard from the Occupants, and the Watcher is clothed in blue and tasked with observing her surroundings.

Everyone ultimately follows the orders of the red Principal. She is closest to ALLMOTHER, and whispers from other clones suggest that she often sleepwalks, muttering to herself about ALLMOTHER.

This hierarchical structure resembles the Platonic ideal of structures idealized by vulgar Confucianism: people know their place in a community and are able to be filial to authority figures, especially to their elders and superiors. Mothers know best: let them decide on what their younger and inexperienced daughters should do.

Did Iris knowingly recreate the patriarchal societies of Han Chinese communities in order to create a matriarchy? It's hard to tell what her intention was at the beginning of the game since she also suffered in her own family and I was just wondering if this was the devs' attempt to allegorize Chinese communities. I put it aside for now.

But regardless, I knew there would always be expressions of doubt and frustration toward authority figures. Whenever contradictions between the official narrative and what people are experiencing emerge, people get angry when their perspectives are denied. And it doesn't help that factional tensions could introduce new complications because they have different visions of what serving ALLMOTHER should look like.

Yet, they all work together -- sister by sister -- to please ALLMOTHER. Iris could be abusive and had the right to beat her daughters up, but working for her made sense: everyone would stop bickering with each other and work together for the common good.

But the player knows better: the first thing they see in the game is Watcher stabbing ALLMOTHER with a shard before they have movement control of their avatar. This is an inescapable conclusion that comes sooner than I expected. I understood why Watcher killed ALLMOTHER because I had already seen Iris's memories: I laughed at her self-deprecating remarks, like how she had a "resting bitch face," but I also couldn't stand how she mistreated Jiao who was her closest friend.

Her disgust with Jiao went beyond what I expected, especially when Jiao copied everything from her. When Jiao dressed up and cut her hair to look like Iris, Iris snapped, unaware of the irony that she would be creating clones to save a dying human race. Jiao clearly saw Iris as a role model because Iris had survived the harsh, racist winters of Canada, and Jiao wanted to adapt. But there was no reciprocity beyond a few hollow words about how things might be better after high school: relations are strained, and it is only when Jiao is gone that Iris finally realizes how much she depended on her.

When Iris became the ALLMOTHER, I saw her as an authoritarian figure. It didn't matter if her loneliness was real; she was hurting her daughters, who in turn felt the need to hurt others. Many of her daughters begged for approval and she wouldn't budge. She could have de-escalated all the tension and bickering if she had bothered. I saw her as the core of all that was wrong with the clone society, and perhaps erasing her would help the society function better.

The violence felt right. I didn't see her murder as shocking anymore. I thought I was almost done with the game, and I ran through the stock phrases in my head to describe what the game was like.

But the game continued.

A cycle -- of what? -- resumes. The march of time parallels the time before. Everything seems to have changed, but the dynamics under the hood are still the same.

I realized that the game was never an allegory from the beginning. It was speculating on a future where Hong Kong had already been absorbed into China and everyone who had fought for its independence had fled. The violent imagery unlocked something in me as the protest imagery became more intense. Desperation coursed through the veins of the clones in the later chapters. They spoke words I've seen on social media in 2019: there was no escaping the references to sacrifice, police violence, and self-immolation. I felt the waterfall of suppressed thoughts about what it means to be Chinese in a post-2019 Hong Kong protest.

The game asked questions no one dared to ask. Too recently, we waved them away. It's a good thing our Discord friends only knew about the incident because of the Hearthstone thing. Imagine explaining how we all got here: you have to start with the fall of the Qing Dynasty, bring up Sun Yat-sen's promise to unite the Communists and Nationalists, lament the Chinese Civil War, and so on. And then, we can finally begin to explain the special and unique circumstances of Hong Kong and how it developed as a British colony before being handed over to China.

It was better to sweep it all under the carpet.

But after a certain point in this game, I saw Hong Kong in everything. The game even encouraged it. I was running through corridors that reminded me of the videos people shot as they ran away from the police. I saw an interrogation that followed the same premises as Gui Minhai's forced TV confessions. Whether the player is reliving memories of Iris and her parents or wandering through the hubs to find a purpose in life, the parallels are everywhere: ALLMOTHER looms over the horizon like China watching over Hong Kong's every move, the soldiers at Iris' school resemble the orange soldier clones patrolling the Orchard, and the game's mothers are unable to connect with their daughters. These aren't just parallels; they are the continuation of a trauma that never ceased and everyone is recreating the Hong Kong and China dynamic over and over again.

There was no going back: protesters and cops, clones and ALLMOTHER, Iris and Jiao. The memory of Hong Kong standing up to China echoes through time and space. When clones talk about burning themselves in protest, they are referring to the doctrine of Lam Chau, a scorched-earth policy born out of panic: the Umbrella Revolution of 2014 failed, so peaceful protest would not work against a China that ignored their cries -- people were now in a corner crying, "If we burn, you burn too."

1000xRESIST isn't interested in exploring the causes of the 2019 protests. Rather, it's interested in the emotions that fueled the violent protests and made them so bloody. It does not romanticize these protests, nor does it downplay the real desperation of the protesters against the government.

It just cries not only for Hong Kong, but for the people who still long for the city even after it's all gone.

Karen Cheung writes in The Impossible City: A Hong Kong Memoir that "it is not Hong Kong that has died, but the imagination of the place we were promised in 1997". Even before the protests, the spaces she used to frequent were disappearing due to gentrification. Artists and movie stars were working for China, not Hong Kong. Cheung describes earlier in the book that

Hong Kong’s capitalism perpetuates an endless reproduction of wannabe oppressors, and with the help of government policies and Chinese money, we—consumers and residents and small-business owners and future landlords—devour ourselves until there is nothing left.

And yet, Hong Kong wanted a myth to define itself. Later in the book, Cheung speculates,

The creators of the myth ask: Who is it that perpetuated the idea of Hong Kong history being the development of a fishing village to an international city? The act of mythmaking, of creating an alternate history, is to assert sovereignty over your own story, when politically you’ve had no say over your own future at all—when the handover was forced onto you. The people of Hong Kong had been stripped of the right to self-determination, with no seat at the table when the negotiations for our fate took place. You are Asia’s world city, an international financial center, an inalienable part of China, the government tells us, the foreign press tells us, Beijing tells us. But if we cannot rewrite our origin story, can we at least reimagine our future?

This future would take the form of finding a way out of becoming "just another Chinese city," to use a common editorial phrase in newspapers and blogs. Flags of the United Kingdom and Colonial Hong Kong were waved in the 2019 storming of the Legislative Chamber. Hong Kong has a bit of Britain in it and their citizens are proud of it: I learned from conversations about the game with a Hong Kong friend that its law had more in common with British common law than with China's, and that its supreme courts still employ British judges. The colonial past was more acceptable than the state capitalist present.

This confuses me as someone whose grandparents suffered under colonialism. The angst they have to feel different, like how Iris hated Jiao dressing up as herself, is just so far from my own experience.

Nevertheless, this identity was always at stake. Cheung describes how, to a certain extent, Hong Kongers saw the city's decline as inevitable. The handover meant that Hong Kong would lose its individuality in fifty years' time, and the dread permeated the atmosphere. The 2019 protests were their last stand against China: they saw themselves as David against Goliath, but in retrospect it looked more like a suicide attack.

At the same time, they were proud of this impossible city they had helped to build. There was something precious in this metropolis that was worth preserving. People dreamed of the utopia known as Hong Kong, even though that dream had long since died. The 2019 protests were, in this light, one last rallying call to protect this dream. They fought SARS with their masks and they're fighting COVID and China with their masks on. China was just the Enemy of the Week. This fighting spirit is worth writing love letters for: Hong Kong has always defined itself against opposition and this is no different.

But 1000xRESIST wants to say something different: it eulogized the death of this once great city. Iris's parents are terrorized by the visions of Hong Kong; her father wants his ashes there while her mother says, "I dream of every night going back home. Haunted by a place that doesn't exist." Their daughter and the player's avatars replay the moving images of a city they've never seen before. This phantom, now a lost future, can bring comfort to those who seek it.

However, this yearning is a drug: Hong Kong was born out of questionable circumstances that would always lead to conflict between it and China. Hong Kong needs China to define itself, and China will always oppress Hong Kong. They are two mothers who loathe each other, just as Iris loathes her mother. In other words, Hong Kong needs an Other to say it isn't Chinese. This abusive relationship is how the dynamics of Hong Kong and China are made.

Iris is probably unaware that she longs for Hong Kong, but her unconscious longing after dealing with so much racist crap in Canada caused her to reproduce the violence when she tried to talk to Jiao or her daughters. She disciplines her daughters in the same way that her traumatized mother disciplined her. She can only emulate and teach the heritage she still remembers. She longs for a home that can truly accept her. But that home has vanished from the face of the earth.

So, Iris suffers. Her daughters suffer. They all suffer from their nostalgia for Hong Kong.

1000xRESIST is about the cycle of diasporic trauma, and that's something I'm not ready to hear about.

The trauma seeps into everything it touches: families, societies, politics, childhood, food, dreams, love, and so on. Everyone overseas wants to recreate their Hong Kong identity as much as possible, even if it means perpetuating the cycle of violence.

Near the end of the game, a character comments that humans are the worst piece of technology because they are "too capable of storing clutter [and] too desperate to hold onto things." If there is a true antagonist in the entire game, it is memory. Humans remember grudges and lost things far better than they are willing to forgive. Memory does not always provide catharsis -- it can instead entrench you further and further. Everyone in the game repeats events beat for beat, much like how the 85-track soundtrack repeats leitmotifs.

In a way, no one has left the city. They are still in the streets and subway stations fighting each other, only this time under a science fiction pretense. The memory of Hong Kong remains and this is how diasporic trauma reproduces itself, even for the people who don't remember it.

1000xRESIST seems to suggest that the listlessness of diasporic children like Iris and her daughters stems from a lack of belonging. They've tried their best to give themselves a sense of purpose by integrating further into their constructed society, but the community lacks an organic structure. Hong Kong is still too close to their hearts and they know whatever they built won't satiate their longing.

But the game fantasizes an ending for them: they must run away from the city they once called home. They have to pack what they can and leave if they want to change. No one can keep everything the same or the violence will continue. Some things have to be locked away.

When I was given the chance to do this for the characters in 1000xRESIST, I was overwhelmed. I had to erase memories and possibilities for a new future. That didn't feel right to me, not because I felt any kind of dissonance with the game's themes, but rather because I felt like the game was attacking my beliefs.

Since childhood, I have fantasized about the reunification of Chinese people around the world. We were all orphaned by our histories, but as China and Taiwan opened their doors to each other, we came into contact with relatives we thought had disappeared. My late grandfather in Jakarta met his younger brother in Taipei, and I remembered tasting local delicacies in Meizhou. I lived in Shenzhen and visited Hong Kong. It felt like we were all becoming one happy family, even though our history was full of bloodshed. We're finally regaining our sense of a Chinese community.

But incidents like the Hong Kong 2019 protests and the general aggression against Taiwan stopped my dreams. I still held onto the possibility that things could change for the better. It had to. Xi Jinping was just a bad apple clinging to power through machismo. The Hong Kongers have probably pushed too many buttons, but there must be a way to get the city back on track. We just had to wait for Xi to die and for someone better to lead the CCP.

So, I had to argue with the logic of the game. I didn't want to agree that what I wanted to do would perpetuate a kind of diasporic trauma, even though I also felt detached from the events in China. I just had to believe. I was still dreaming of Hong Kong in my own way. I saw Hong Kong as a place where we could all gather and eat yum cha together. Abandoning that possibility was too grim, too much for me.

And it was at that moment that I realized who the target audience of this game was, at least the audience that would be most receptive to its message. It certainly wasn't for Chinese Indonesians, but it also wasn't for Hong Kongers who were still fighting China on the ground. More tellingly, I don't think it's even for the diaspora and refugees directly affected by the 2019 protests. I imagine they are still too close to the events to take the game seriously.

This game is for their children, the generation that has not been born yet.

I reiterate: the 2019 protests are too recent for the game to be impossible for all of us to analyze. I don't think anyone, let alone me, can articulate what the game is trying to do because Hong Kong is still with us. Iris hasn't been born yet. We have to wait until 2047, when Iris is a high school student wondering what the hell Jiao wants from her, for the game to make sense.

This is a game for the Irises who will ask us why we are still haunted by the phantoms of Hong Kong and our continued failure to build a home. They will want answers as to why they cry for a city they never knew existed. They will be looking for a way out of this loop that we Chinese diaspora have created to trap ourselves.

1000xRESIST teaches them how to run away from home and become independent from our traumas. They must learn to resist a thousand times our dreams and hopes if they are to carve out a better future for themselves. They must pack up what they need and leave. They must choose their ending.

As for me, I wonder what I should say when I see my 1-year-old niece, who may become an Iris in the future, questioning the premises of my diasporic trauma. Will I be like my parents, who told me to remember our heritage even though I didn't care one bit about what they were saying? What if she reads my post about the game and argues with my reluctance to accept the game's message? If she told me I was ancient history, I'd probably have to agree.

It's difficult for me to accept the game's conclusions: Hong Kong was a symbol for me, even though I know better. I cannot fight the irrational part of the brain. I wanted Hong Kong to somehow overcome China, even though I know it's impossible.

Writing this essay has made me rethink how I view my diasporic perspective. I don't expect most people, especially non-diasporic people, to understand my struggle, and that's okay. I wanted to navigate my feelings about being a member of a diaspora and what it means to give up the dream of returning to one's motherland.

And there is no shame in seeking recognition from a motherland (or actual mothers). There might even be degrees: not all diasporas and refugees have to follow the same standard this game gives, depending on the circumstances.[^1] I think for Chinese diasporas, we want to be loved, understood, and accepted by the people who gave us birth. The desire to return to our homelands is understandable, but it should not be not at the expense of the children who will replace us.

Not to mention that I think Confucianism and our upbringing often stress children to remember, to revere our traditions, and to memorize our historical traumas. It's still important for them to learn a bit about our history, but this game reflects how they can inherit our traumas. I wish I knew how to balance our priorities for this.

1000xRESIST is hard to write about. I can think of more things to say, but it will never feel complete or satisfying. I am not ready to talk about this game yet. All the conversations I have with Hong Kongers, Chinese people, and players are not enough. It's too visceral, it reopens many troubling lines of inquiry, and it leaves me with a visible gash in my chest. It hurts.

And that's why I think people, especially Chinese and Hong Kong diasporas, should play it. We need to remember the heartache in order to prepare ourselves for when our children ask us, "Why did it have to be this way?" Whatever answer we give, we have to realize that what they will arrive at is an answer they will have to create out of our answers.

This is their story, not ours. They can decide how they want to leave Hong Kong and China. I trust them to find a satisfactory answer.

[^1]: Initially, I didn't want to bring up how articles about the game often bring up the current Palestine protests as a common corollary. It makes sense for writers to ground readers in something more familiar to them. That said, I don't think the message (as I interpreted it) would apply to survivors of settler colonialism. The brutality of Israel and the displacement of Palestinians are not comparable to China and Hong Kong, even though both examples are violent. While Palestinians abroad might be considered a diaspora, I don't think they would resonate with this game's message to the Chinese diaspora to pack up and leave. Even if one agrees with the message of the game, Palestinians should get their homes back. Diasporas have unique needs and problems. This is a pretty important distinction that I hope more writers who want to bring up Palestine when talking about this game will respect.